The Fate of our Species in an AI-Infused Planet

© Howard Gardner 2026

Perhaps in every era—or at least in many eras—reflective individuals wonder whether their era is special—disruptive, and if so, in which benign or malevolent ways.

Ours is no exception. Indeed, in the era of nuclear power (which can be mobilized for constructive or annihilatory ends), mass communication of all manner (salutary or destructive), powerful medical interventions alongside globally-spreading and sometimes fatal viruses, and—above all—forms of computing that may soon culminate in Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), many of us are attempting to put together the pieces. In this essay, I seek to synthesize facets of my biography, my scholarship, my observations, my hopes, and my concerns.

If you know my scholarly work at all, you are likely to be familiar with my theory of multiple intelligences—the claim that the human mind is best described as a set of relatively independent computational devices (Gardner 2026). Standard IQ tests gauge linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences, but give short shrift to other cognitive capacities, ranging from musical or mechanical abilities to the understanding of others or of oneself. Naturally, when one considers AI or AGI (as well as animal and perhaps plant intelligences), it is appropriate to consider the strengths and limits of non-human computational systems (Gardner, Furuzawa, Stachura 2025). Yet, paradoxically, when I chose to write a scholarly autobiography, I found that “MI” theory (MY theory) was of little use (Gardner 2020). Turns out that I am a typical academic scholar—competent in the standard IQ measures, with a modicum of musical intelligence tossed in as a bonus.

But I came to realize that my intellectual strength—such as it is—lies in synthesis. I read widely and absorb information broadly and then assemble the resulting panorama in ways that make sense to me, and at the same time, may also prove helpful to others. (Read more on this at my blog dedicated to synthesizing here.) An author primarily of lengthy manuscripts, rather than of brief articles submitted to academic journals, I’ve written over thirty books—and many of them are syntheses—Creating Minds, Leading Minds, Art Mind and Brain, The Disciplined Mind, the list goes on.

A surprise: When I examined the literature in psychology and education, I found almost no rigorous analyses—let alone suitable experiments—that illuminate the synthesizing mind. The explanation seems simple: While one can test in a few minutes for an experimental subject’s ability to solve analogies or to prove geometry theorems, synthesizing by its very nature takes time, motivation, testing out options, feeding forward and backwards. I know—because that’s been my work for over 60 years!

While I may have believed that I was “done” with intelligences and synthesizing, I came to realize, on the contrary, that I had just begun to understand synthesizing. And indeed, since 2020, when my memoir was published, I’ve written over thirty essays on this topic. (You can read them here.) And I suspect that I am not done yet!

Not sure quite how and why, but I soon turned my attention to times and places where the need for synthesis was acutely felt and then deftly addressed. I found myself studying the Axial Age. (Read the resulting blog here.) And indeed, it appears that era—roughly from 800 BC to the beginning of the Common Era—constituted an unprecedented time. Alone or in small cohorts, a significant number of thoughtful human beings began to reflect, discuss, and communicate about the nature of our planet, our species, our minds, our spirits—and sought to put together (typically in text) their impressions and conclusions in ways that made sense to themselves and to other of their fellow human beings.

There may have been other periods that rivaled the Axial Age. Indeed, just reflecting on the civilization that we call Western, it seems appropriate to think of the Renaissance of the 15th-16th century, the Enlightenment of the 18th century, and possibly the Industrial or Informational Ages of more recent times as viable candidates.

If you’d asked me a decade ago what was special about our era—whether in some sense it was as pivotal as the Axial Age—I’m not sure how I would have responded. But two events have propelled my current thinking. One—already alluded to—is the explosion of AI and the very real likelihood of AGI. The other is the realization that we may have come to the end of the era that I—tweaking its customary connotation—dub the Anthropocene: the era during which members of our species presided over the planet and quite possibly achieved unique status in the solar system, the galaxy, maybe even the universe. (Read my blog on the end of the Anthropocene here.)

Now, well into my ninth decade, it’s clear that I won’t learn the end of the story…nor in all likelihood will my children, grandchildren, students or grand-students. But for that very reason, I want to put forth how I hope the human epoch may continue—and perhaps even flourish.

Shifting frames: Two Powerful Experiences from my Childhood

1. A frigid and memorable morning

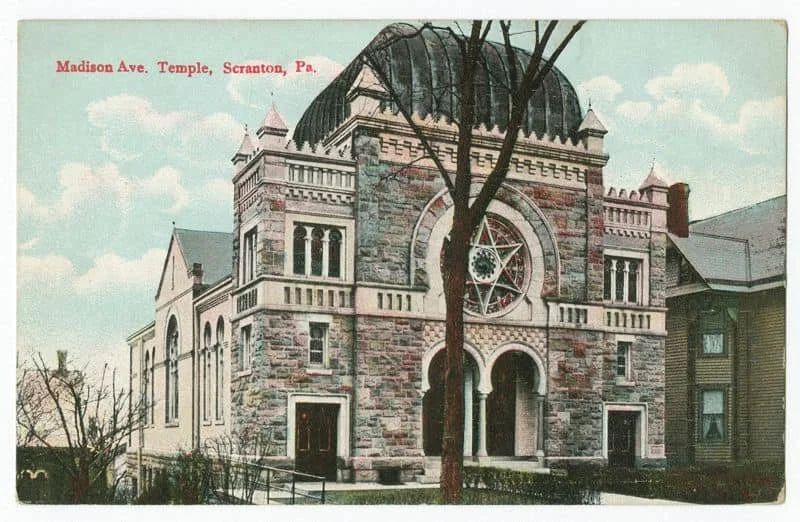

As a child, I regularly attended Saturday morning services at my family’s temple—the Madison Avenue Temple in Scranton, Pennsylvania. I did this because others did so; because I was preparing for my “bar mitzvah” at age 13; and because I was an obedient child. I never questioned that weekly routine.

One Saturday in December 1955 when I was twelve, it was snowing a great deal. Buckling up and buckling down, I trudged the dozen blocks from our home on North Webster Avenue to the Temple and sat down on a pew, waiting for the service to begin.

But no one else was there! Well, no one except Rabbi Erwin L. Herman. To my considerable surprise, Rabbi Herman went through the entire service of perhaps 45 minutes—note I did not write “ran through”…because he proceeded at the normal pace!

Afterwards, I approached Rabbi Herman and asked him: Why, since no one else was there, had he nonetheless conducted the entire ceremony? Without any need to ponder, Rabbi Herman simply responded, “God does not count house.”

Seventy years later, that exchange remains with me, vividly. Indeed, it has probably molded more of my subsequent behavior, standards, and consciousness than I can appreciate. I have a very strong sense of duty in several sectors of my life—to put it in Freudian terms, a powerful superego.

Once I left the Scranton public school system—first attending a boarding school, then going away to college—religion played less and less of a role in my life. And much the same thing can be said about the status of God—I did not pray, I rarely thought about Matters Divine. (I remember posing questions to myself about heaven, evil, and the possibility of an afterlife, and concluding that none of the prevalent answers satisfied me.) When at my parents’ home or visiting with relatives elsewhere, I might still go to temple and commemorate the High Holidays. But whatever role Judaism might have once played for that 12-year-old on a December morning in the 1950s, religion and God were no longer central for me—and with every passing decade, they have diminished in my daily consciousness.

2. Seven years with peers

Other aspects of my youth have also left significant marks. Like many other young American males growing up in the 1950s, I was part of the Scouting movement. Indeed, I was a Cub Scout for three years, a Boy Scout for four years, and then became an Explorer. At a young age, about the time of my bar mitzvah, I also became an Eagle Scout. This status entailed accumulating numerous “merit badges”—on topics ranging from “birding” to “bookbinding”—and completing at least twenty overnight hikes, complete with pitching a tent, starting a fire, and trying to sleep next to innumerable ants. Since my scouting days, I have become aware of some of the malign aspects of that enterprise—and indeed, recently, the Boy Scouts of America officially changed its name to “Scouting America” and now welcomes girls as well as boys.

As with formal religion, scouting has faded from my daily consciousness—and yet, I believe that it was an equally powerful formative experience. Over the course of my decade in the scouting movement, I learned to get along with a wide variety of peers, to compete, but also to cooperate, with others, to solve practical problems, and to carry out a range of projects—some in an afternoon, others over the course of a summer or a semester.

Why this trip—this detour—down two of my own “memory lanes”? If you’ll bear with me a bit longer, I’ll seek to tie these threads together.

Marshall McLuhan

Once I left Scranton, scouting, and spiritual life, I majored in a field called “Social Relations” at Harvard College and became a social scientist. Wielding the tools of my trade, I sought to understand the era in which I was living and the ways it related to the past—and possibly, to the future. Aiding these reflections was the polymathic thinker Marshall McLuhan (1964). Perhaps best known for his quip, the medium is the message, (and for his walk-on appearance in Woody Allen’s movie Annie Hall), McLuhan provided a helpful framework.

McLuhan contended that the powerful media of communication in an era—in his time, radio and television—powerfully (if surreptitiously) shape how messages are received, understood, and ultimately constitute our worldviews. In a memorable example, McLuhan contrasted the experiences of those who viewed the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon presidential debate on television with the experiences of those who listened to the same debate on radio. With respect to viewers on video—a medium that softens images and favors informality—the “cooler” Kennedy was seen as the winner. In contrast, for those who listened on the radio—a “hot” medium which demands concentrated attention—Nixon’s more pugnacious style and delivery triumphed. (Note my blog on McLuhan’s framework and this debate here.)

As a field of study, computer science began in the middle of the 20th century (just after McLuhan had developed his pivotal conceptualization). Its initial technologies were based on simple computations—expressed as zeros and ones—which captured the way that human beings consciously reason, play chess, solve mathematical and logical problems. But in the 1980s, the building blocks of the field shifted dramatically. Computational models came to be fashioned in the manner of neural networks. Concepts and operations were constructed on the basis of copious examples, involving multiple and often imperceptible dimensions. These models more closely resembled the way that human beings (as well as other organisms) recognize patterns and build upon them, sometimes in unexpected—and even in inexplicable—ways (Gardner 1985).

Once the phrase artificial intelligence had been coined, the contrast between the intelligences of human beings, on the one hand, and the capacities of mechanical or digital devices, on the other, became salient. And when computers proved able to surpass human beings—first in chess, then in the far more complex game of “Go”—the power of artificial forms of intelligence was increasingly acknowledged. But only in the last decade have both experts and lay persons (like me) confronted an awesome possibility: the likelihood of artificial general intelligence or AGI—computational entities and systems that are smarter than human beings, and perhaps, even smarter than the entire human community.

This realization has taken me back to Scranton, to the roots and experiences of my childhood—in my case, membership in a religious community (Madison Avenue Temple) as well as membership in a community of peers and youthful mentors (the Scouting movement). From these two “cases,” I acquired many of the values and much of the lore that would guide my own life and help me to relate—hopefully appropriately—to other persons. Via religious training, I became familiar with the Ten Commandments, the Golden Rule, and other Biblical and religious guides to ethical, moral, and communal behavior. Via Scouting, I mastered its oath and its twelve commitments (“A scout is: trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean and reverent.”). I also sought to embody these virtues in my relations with peers and to transmit those values to younger scouts. Fortunately, these values were reasonably consistent with those I observed and absorbed from my family—otherwise, I would have felt very conflicted.

To this point, I’ve discussed aspects of my early life, as well as my conspectus as a scholar. Just touched upon has been the work for which I am best known: an educator who introduced the idea of multiple intelligences—very briefly, the claim that we human beings have a number of relatively separate intellectual faculties. Our multiple intelligences are not well captured by standard IQ tests, but they prove important in schooling, as well as in the less formal tutelage secured from parents, family, and neighbors in a community. An “MI” approach helps individuals to discover their strengths and to draw aptly on them for a productive life—in the workplace, leisure pursuits, and the broader community.

As a researcher on intelligence, I have perforce been interested in how others make use of this concept: Daniel Goleman’s (1995) concept of emotional intelligence; the study of the intellectual capacities in different animal species and even plants; and more recently, the increasing power and capaciousness of forms of AI and AGI. (Read “Who Owns Intelligence,” co-authored by myself, Shinri Furuzawa, and Annie Stachura here.) I believe that much of the educational system that we take for granted in 2026 will need to be rethought—and perhaps even fundamentally overturned—in a world where so much of intellectual life and labor will be done better— perhaps immeasurably better—by various forms of artificial intelligence. (Read my two recent blogs on education in the era of AI here and here.)

And now, at last, I’ll attempt to bring together the various strands of this wide-ranging discourse. Whatever happens in formal education (K-12, higher education), however much of basic literacies and the standard disciplines are effectively conveyed by AI, I believe the following: Our social, ethical, and moral lives cannot and should not be consigned to any artificial entity, no matter how social, how smart, perhaps even how wise—this entity appears to be, or claims to be. At most, artificial strands of intelligence may lend a hand—but to tweak an apt phrase “the ball remains in our court”—the court of homo sapiens.

Indeed, as the Axial Age (and its later possible iterations) fades from memory, as the era known as the Anthropocene may itself be concluding, as a species we have an awesome—in the sense of awe-inspiring—task. We need to understand, preserve, and pass on to our descendants what is most valid and most valuable from our experiences as a species in the last few thousand years; to continue to engage in those pursuits that we find productive and enjoyable, even if AIs can carry them out more deftly; and most important, if still elusive, to design and attempt to realize new utopias which are worth aiming for and perhaps achieving—let’s dub them “Universal Utopias.”

Here's where the processes and the insights conveyed by formal religious orders (and less formal institutions like scouting) become crucial. As a species, we human beings need to find ways to recognize and build upon our common membership—the current embodiments of the bodies, minds, and (yes) spirits—that have characterized us for thousands of years, and that were explicitly recognized and built upon, perhaps for the first time during the Axial Age.

Personally, I believe that the body of beliefs and practices termed humanism provides the most promising approach. As described by Sarah Bakewell (2023) in her excellent synopsis, humanism entails rational inquiry, cultural richness, freedom of thought and a sense of hope. I’d like to think that all members of our species could subscribe to these strands of thought and action. But it’s well known that most human beings belong to one or another formal religion; it is unreasonable to expect that our fellow members of our species will simply drop Catholicism, Buddhism, Islam, Shinto, Hinduism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and/or the numerous sects of Protestantism in order to embrace the humanistic vision that Erasmus and his followers put forth two thousand years after the Axial Age.

Nor is it necessary that our fellow human beings should do so. On the contrary, I welcome many of the ideas, practices, and prayers that the aforementioned religious entities have created and nurtured over many centuries.

But one (admittedly very challenging) step is essential. Members of our species should acknowledge that these various formal religions are valid and worth embracing, so long as these religions recognize—and do not attempt to critique, to attack, or all too often, to annihilate—other seemingly competing religious orders. We cannot afford to have more Crusades, more Hundred Year Wars, more World Wars, more Regional Wars at a time when the survival of our planet and our species is fragile—and when aspirations of a better life for all living entities are at stake. We can take inspiration from Mohandas Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King Jr.—each personally devout but each willing to work peacefully with all other human beings, irrespective of the specific religious identities or humanistic credo.

It is very easy—and perhaps tempting—to think of the current threats to our species and planet as frightening, as deadly, as conclusive—and, hence, to reach for our weapons, on the one hand, or to bury our higher aspirations, on the other. But while recognizing these threats, as members of the human species, we can also acknowledge our achievements, our aspirations, and our common threads. We can attempt to build a better and a more secure and more unified planet for those who come after us—and then, our jagged journey spanning thousands of years will indeed have proved worthwhile.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to my colleagues at Harvard Project Zero for their comments on earlier versions of this blog. Special thanks to Annie Stachura and Ellen Winner for many useful suggestions.

REFERENCES

Bakewell, S. (2023). Humanly possible: seven hundred years of humanist freethinking, inquiry, and hope. Penguin Press.

Gardner, H. (1985). The mind’s new science: a history of the cognitive revolution. Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2026). Frames of Mind. Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2020). A synthesizing mind. MIT Press.

Gardner, H., Furuzawa, S., Stachura, A. (2024). Who owns intelligence? Reflections after a quarter century. MI Oasis. https://www.multipleintelligencesoasis.org/blog/2024/10/22/who-owns-intelligence

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media. McGraw-Hill.