Children’s Museums: A Valuable Model for Education in the Era Of AI

© Howard Gardner 2025

Around 1975, I fell in love with children’s museums. Of course, they had been around for a while—but it was the Boston Children’s Museum—as conceived and curated by Michael Spock (the son of illustrious pediatrician Benjamin Spock)—that captured my heart. First located in a rambling house in Jamaica Plain, later in its own far more generous (even grand) quarters on the Boston Waterfront, the Boston Children’s Museum contained a wide gamut of exhibits, structures, games, challenges—all of which were child-friendly, many of which proved attractive to children (and indeed adults) across the age span!

What particularly attracted me was that there was no prescribed route—no must-see, or must-do, or must-avoid exhibits. Rather, all young people had the option of going to an exhibit, a display, a corner or nook to spend as much time as they’d like, or move on to another exhibit—and, of course, revisit the museum on numerous occasions—so long as their parents or guardians had the stamina (“Do we have to go home now?!”) and could cover the modest fees.

As a fan, I joined various organizations that promoted children’s museums and tried to help when I could. I visited children’s museums around the world. I loved the phrase, “No one flunks children’s museums!”—and I often invoked it.

But I also edited that sentiment in my own mind, and occasionally aloud. For sure, children should return to specific exhibitions as often as they’d like—but they should be encouraged after a while to try something new with that particular display or to explore another object or nook as well. Some children might return to the water bubble display numerous times—but after a while, they should be encouraged to assume a different stance or try a different manipulation with the water. And it would be the job of parents, older siblings, floor guides to gently but firmly encourage the child not simply to perseverate, but rather to explore.

Having four children (now quite grown up) and five grandchildren (ranging from kindergarteners to collegiates), I have continued to visit museums—not just children’s museums, but also science museums, computer museums, art museums, museums of natural history, and other genres. Having served on a few boards, I also know a fair amount about their policies, their constraints, and their exhibitions—and of course, these vary greatly and instructively from one another.

But of late I have come to a conviction:

Children’s museums—an invention of the 20th century—also provide a key to optimal education in the 21st century, at least in the United States, and perhaps in other regions of the world as well.

Acknowledging that this phrase is hyperbolic, I would claim that the curriculum of American secondary schools was largely created at the end of the 19th century, by the so-called Committee of Ten. That small group of educational leaders determined that in American schools (especially secondary, but also middle schools), all students should basically study the same basic curriculum:

Latin

Greek

English

Modern languages

Mathematics

Physics, astronomy, and chemistry

Natural history

History, civil government, and political economy

Geography

The work of the Committee of Ten was supported half a century later by leading members of the Harvard faculty. In 1945, under the direction of President James Bryant Conant, this group (all men), outlined General Education in a Free Society—essentially the curriculum of a half century earlier, divided into sciences/mathematics, social studies, and language/humanities.

Not only has this curriculum remained remarkably standard—stable and static. It dictates—or at least casts a very wide shadow upon—the ways in which students and schools are compared with one another, admission to competitive colleges and universities is determined, and even forms the basis of the major international comparisons.

This curriculum has become so prevalent that it’s hard even to imagine a very different kind of curriculum around the country and—indeed—around much of the world.

Enter children’s museums!

Let’s say that, instead of dictating what should be taught, when it should be taught, and how it should be taught, we instead gave considerable agency to children.

Let’s say that we thought of education from early childhood through adolescence as a space where young people could gravitate toward what they are interested in, pursue it as they would like, and gain competence, even expertise in that area.

Note: This is how we think of hobbies. So long as a child does alright in school, we are content—even pleased!—if that child plays an instrument, masters a sport, is absorbed by Minecraft, Scratch, chess, or video games—provided that these pursuits of passion are not damaging to head, heart, or psyche.

Another Note: Such a stance has also characterized the more extreme forms of progressive education—Summerhill, British style, The Sudbury Valley School, American style.

The Sudbury Valley School in Framingham, Massachusetts

A 21st century stance, as I see it

Building on the child’s (now seen as a student’s) interests and strengths, let’s use those predilections as “entry points” to a wide range of subjects, disciplines, forms of expertise.

Take, for example, the interest in one’s own family—its roots, its history, its expanse—as captured in Henry Louis Gates’ Finding Your Roots—or as encouraged by Project Zero’s Open Canopy, or its predecessor Out of Eden Learn.

As we enter the second quarter of the 21st century…

By virtue of Large Language instruments, as a point of departure, every child can use interest in family or clan or neighborhood to explore a gamut of subjects, topics, platforms. Sticking with the Finding Your Roots prompt, children can find out about the biology and chemistry that they share with family, with neighbors, with peers in different cultures—and also, with hominids or pets. They can explore the geography and history that they’ve traversed or heard about—the costs, purchases, finances that they or their family has dealt with, the statistical probabilities that things could have gone another way, the artistic interests, skills, hobbies pursued, whether those could be pursued further today, and the like.

The list of connections to one’s roots is as broad, as wide, as universal, as one can imagine.

And if something is missing, it takes only a prod or two by an educational influencer to catalyze its appearance and its growth.

Of course, one’s family history is just one of a myriad of entry points. As specimen others—the foods one likes, the media presentations to which one gravitates, the hobbies of their neighbors, the news of the day or the night—the catalogue of “entry points” is unbounded.

You may well be thinking: what’s to keep the user involved with these explorations—rather than simply repeating the same pattern, or, alternatively, just switching to another game, another theme, another preoccupation?

Here, I think, we can make use of another tool of psychology—as pioneered by Ivan Pavlov and fine-tuned by B.F. Skinner. Well-fashioned patterns of reinforcement should keep the student’s interests within the general area (one’s family and its link to various themes and disciplinary tools).

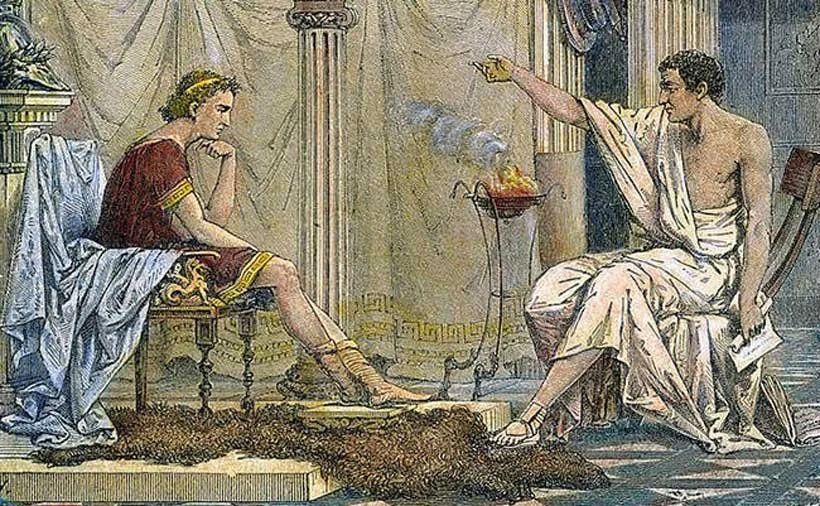

Aristotle and Alexander the Great (Illustration by Charles Laplante, 1866)

In times past, Aristotle could offer such a panorama to his student Alexander the Great; European royalty could have a suite of tutors for the heir apparents; the fabled 19th century student at Dartmouth could sit at the end of the log, while skilled educator Mark Hopkins was seated on the other.

But not, alas, 99.9% of the world’s population…

Until our time…

I hope I have aroused your curiosity and whetted your imagination. Large Language instruments can prompt and respond to the interests, the predilections, the curiosities of the student, and provide the educational and pedagogical tools and materials to pursue these further…of course, opening them to “real world” options, which could include visits to nearby museums, libraries, Disney-type worlds and other educational establishments—indeed, to the local college or university. And of course, there can and should be a role for more knowledgeable individuals (be they teachers, coaches, or just older or more advanced peers)—but I suspect that much of the burden that individual teachers have had to bear (often with dozens of students competing for attention in their classrooms) will now be assumed by these instruments.

Indeed, perhaps it is time to suggest a role for individuals with particular skills and knowledge for the period ahead. Those individuals—floor guide style—can glean a child’s interests, and—teacher-style—can also suggest promising paths forward, perhaps directing each child to congenial AI paths. For now, call that role an “AI Educator Guide.” (Better names welcome!)

Give me an entry point, and AI can open up worlds

As a dividend, the educational approach that I’m describing fits well with the major educational implications of MI theory—the theory of multiple intelligences that I developed over forty years ago.

I have always resisted the urge to dictate particular curricula. Instead, I have said that “MI theory” has two major educational or pedagogical implications:

Personalization/individualization: Find out as much as one can about the individual learner and present lessons and materials in ways that are optimal for that learner.

Pluralization: Decide what’s important, fundamental, in a particular area of learning, and present such materials in more than one way, ideally in several ways. Not only do you reach many more students, more effectively; but you also reveal that a teacher, a parent, even a guide who can present a lesson in only one way has a suboptimal grasp of that material.

In summary…

For me, children’s museums were love at first sight. On the other hand, when I first learned about AI/AGI, I found it somewhat threatening…might it become a tyrannical “Big Brother”?

Now, however, I think that a wedding, a melding of the power of artificial intelligence to the educational magic of children’s museums could be a win-win—for all of us…and well into the future. One starts with a young person’s interests and provides meaningful links to the strands of knowledge that are valuable and valid as we move into the middle of the 21st century.

Here's to AI Educators!

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments—as well as their intriguing challenges—I thank Kirsten McHugh, Annie Stachura, and Ellen Winner.